OUR CASE

With the EVD inserted and the aneurysm secured, Katherine was admitted to the intensive care unit intubated for ongoing management.

ESSENTIAL SUPPORTIVE CARE IN THE ICU

Recent guidelines at least provide consensus on management, even if evidence is lacking for individual components.

Treat pain, treat nausea

> Pain and anxiety must be treated, for obvious reasons as well as to avoid hypertension and rebleeding.

For non-intubated patients analgesics like paracetamol, tapentadol and opiates usually suffice; NSAIDs may be useful but the slight effect on platelet function risking bleeding should be considered.

Intubated patients usually receive opiate (fentanyl) infusions titrated to pain

Sedation is different to analgesia and intubated patients usually require propofol infusions to tolerate the endotracheal tube.

> Nausea should be aggressively treated as vomiting raises blood pressure and ICP

Enterally feed, with sufficient protein

There’s not high quality evidence guiding nutrition post-SAH.

There is weak evidence that patients with SAH have an increased resting energy expenditure, with potential benefits of high protein diets with adequate minerals for neurofunctional recovery existing (1, 2).

Given this, ensuring adequate caloric intake with good amounts of protein and minerals is likely suitable in post-SAH patients until better evidence becomes available.

When patients are having repetitive daily DSA’s for radiological vasospasm, this can significantly interfere with nutrition. This should be considered and calorific and protein requirements must still be met.

Start with mechanical, use chemical after aneurysm secured

Patients with aSAH are at increased risk of developing a DVT or PE

Mechanical thromboprophylaxis is commenced in all patients prior to securing aneurysm.

Subcutaneous heparin/ enoxaparin is commonly commenced after the aneurysm is secured (in consultation with Neurosurgery).

Recent evidence would suggest that mechanical thromboprophylaxis (with pneumatic calf compression devices) provides no additional benefit to chemoprophylaxis alone for most ICU patients. Hence, mechanical devices can likely be ceased following commencement of chemoprophylaxis.

The decisions surrounding thromboprophylaxis are centre/surgeon specific, so best to follow your instituitions practice.

Nurse head up (>30 degrees) position where possible.

Mobilise low grade aSAH

For 30 degrees head up:

- Weak evidence suggests this is associated with reduced risk of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP).

- There is some suggestion that having the head at 20-30 degrees improves ICP, so may have some role in patients with intracranial hypertension.

Against

- Despite several small exploratory studies, no head position has been shown superior over another, in terms of maximising cerebral blood flow and minimisng vasospasm or most importantly – patient outcome.

- Similarly, there is no strong evidence demonstrating superiority of head up positions in other aspects of neurocritical care

Although there is no convincing evidence for this practice, in the absence of high quality research, a head up position of 20-30 degrees is likely not to be harmful and has some potential to minimise VAP and may reduce ICP

PPI often given; best practice is unknown

Stress ulcer prophylaxis (SUP) with a PPI or H2RB is given to most ICU patients

SUP with pantroprazole reduces clinically important GI bleeding in ICU patients (see SUP-ICU trial)

H2RB may have benefits over PPI for SUP (see PEPTIC trial) though best to follow your local guidelines for which agent to choose

BGL 6-10 mmol/L (110-180 mg/dl)

No strong evidence exists for BSL control in aSAH patients specifically.

However, strict glycaemic control has been shown to have worse outcomes for ICU patients in the landmark NICE-SUGAR trial.

Extrapolating from the NICE-SUGAR trial is probably safe in the absence of alternative evidence, so best to aim between 6-10 mmol/L

Optimal target unknown.

The optimal haemoglobin threshold for transfusion in SAH is still under investigation and will hopefully be clarified in the SAHARA trial which is ongoing at present

Current thinking:

- <80 g/l transfuse (to increase DO2)

- 80-100 g/l site/clinician/patient factor dependant

- >100 g/l avoid tranfusion: liberal transfusion may be associated with worse outcomes (secondary to increased blood viscosity and cerebrovascular resistance)

Watch this space!

Optimal target unknown

Aim for high normal oxygen saturations in all patients, particularly if at risk of vasospasm.

Aim for normocarbia in ventilated patients (prophylactic hyperventilation may exacerbate cerebral vasospasm)

For some patients with chronic respiratory disease and a hypoxic respiratory drive, a lower oxygen saturation target may be appropriate

Corticosteroids

> Corticosteroids are not required unless there is evidence of adrenocortical insufficiency

Statins

> No evidence of benefit

Magnesium

> No evidence of benefit

Trial eligibility

Its always good to check with your department whether the patient is appropriate for enrolling in trials

Appropriateness of Interventions

Always consider the patient and their families views.

For example, with an elderly patient who has a with a high WFNS grade aSAH and previously expressed wishes of not wanting to live with significant disability or dependence, it may not be appropriate to pursue aggressive interventions.

TARGETED THERAPY

Nimodipine

The only medication that has been shown to improve neurological outcomes following aSAH (33% RRR of poor neurological outcome).

> So great we’ve made a separate page about it if you’re interested: NIMODIPINE

In brief:

> Mechanisms by which nimodipine improves outcomes is unknown

> Can be given orally or intravenously, no advantage to IV administration unless PO not possible

> Standard nimodipine dosing is 60 mg every 4 hours PO (20 mcg/kg/hr IV) for 21 days

> Although preferentially selective for cerebral vessels, patients often have some hypotension related to peripheral vasodilation.

> Hence patients often require noradrenaline and intravenous fluids to maintain blood pressure targets whilst on nimodipine.

Nimodipine is not indicated in traumatic SAH.

Preventing Complications

The most common complications of SAH include re-bleeding (particularly in patients with unsecured aneurysms), delayed cerebral ischaemia (DCI), hydrocephalus, infection (including ventriculitis), biochemical abnormalities, seizures, drug or alcohol withdrawal.

There are a number of strategies to prevent these complications, particularly DCI.

As stated above, nimodipine significantly improves outcomes.

All patients, unless strong contraindication, should receive nimodipine.

For more detailed information please refer to this page: NIMODIPINE

Aim:

- Avoid hypotension to prevent vasospasm and maintain cerebral perfusion pressure

- Avoid hypertension which will increase the risk rebleeding from an unsecured aneurysm

There is no firm evidence for optimal BP targets, however the values below are reasonable aims

- 100-140 mmHg prior to securing aneurysm

- 120-150 mmHg following securing of aneurysm

Some centres use prophylactic hypertension in the hope this reduces chances of DCI, e.g.

- 140-160 mmHg if radiological vasospasm identified on DSA

For hypotension

- Use isotonic crystalloid to achieve euvolemia

- If low BP and euvolemic then vasopressor i.e. IV noradrenaline

For hypertension

- Short acting antihypertensives e.g. hydralazine, clevidipine

- Avoid glyceryl trinitrate and other vasodilators which may increase ICP

Follow local guidelines/policies.

Aims:

- Maintain euvolemia

- Avoid hypovolemia: increased risk of vasospasm

- Avoid fluid overload which worsens mortality, causes pulmonary oedema and other organ dysfunction

Choice of fluid

- 0.9% saline or other isotonic fluids such as Plasma-Lyte 148 are reasonable fluid choices

- Hartman’s (CSL) and other hypotonic fluids should be avoided.

- Adjust for fluid balance, fluid status and electrolytes.

Keep Na+ > 135 mmol/L

Hyponatraemia commonly occurs post SAH (up to 50% patients), mostly attributed to cerebral salt wasting and SIADH; differentiating these can be hard and makes little difference.

Hyponatraemic patients have increased relative risk (x3) of DCI.

Therefore monitor sodium closely.

> Prevent serum Na+ < 135 mmol/L while maintaining euvoleamia

Management strategies:

> Minimise free water intake (e.g. allow only fluids containing sodium)

> Aim for euvolemia (note: fluid restriction increases risk of hypotension and vasospasm and has no role in post SAH hyponatraemia)

> Replace sodium with hypertonic saline (e.g. 30 ml/h 3% HTS) or salt tablets (e.g. 1200 mg TDS)

> Fludrocortisone (e.g. 0.1-0.2 mg BD) may prevent natriuresis if hyponatremia persists.

> For refractory cerebral salt wasting consider oral urea (e.g. 15 g PO BD)

Target normothermia (36-38C)

Fever is an independent risk factor for poor outcomes and development of secondary brain injury.

Management strategies for normothermia:

- Paracetamol 1g QID

- Exposure and surface cooling techniques (e.g ice packs, fans, cooling blankets, non-invasive precision temperature management systems)

- Consider NSAIDS, taking into account potential for anti-platelet effects affecting intracranial bleeding, renal injury and GI bleeding risks

Note: fever may also represent infection and septic workups should be completed for febrile patients.

Delirium is common and preventative strategies should be implemented.

Delirious patients are at greater risk of pulling out their essential lines and tubes or causing these to become infected.

Management of delirium may require physical and pharmacological measures.

Suggestions for managing delirium in neurocritical care

Seizure Prophylaxis

Seizure-like episodes are common (up to 1/3), though are thought to not be epileptiform in origin and may be the result of the sudden rise in ICP

No RCT has been performed to help guide decisions on prophylaxis or treatment of seizures.

As such, there is no consensus regarding

- The need for anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs)

- The best AED to use

- Which patients should receive prophylactic AEDs

- The optimal dose or duration of treatment.

Risk factors for post-SAH seizures:

- Increasing age (> 65 years)

- MCA aneurysm

- Volume of subarachnoid blood/thickness of clot

- Associated intracerebral or subdural hematoma

- Poor neurological grade

- Rebleeding

- Cerebral infarction

- Vasospasm

- Hyponatremia

- Hydrocephalus

- Hypertension

- Treatment modality, see coiling vs. clipping

Which anti-epileptic drug?

Levetiracetam is slightly less effective than phenytoin for short term seizure control but may carry better long term outcomes and fewer side effects.

If a prophylactic AED is deemed appropriate, levetiracetam 500 mg BD for 7 days is a popular, albeit non-evidence based regimen.

The risk of rebleeding is greatest within the first 24 hours (up to 15%) for unsecured aneurysms

The mainstay of prevention is therefore prompt securing of the aneurysm (clipping or coiling) as previously discussed

Bed rest and hyperdynamic therapy (hypertension, haemodilution, hypervolaemia) does not prevent this

Antifibrinolytic therapy (e.g. tranexamic acid) has been shown in one non randomised study to reduce incidence of early rebleeding when there is a delay in securing an aneurysm (e.g. patient transfer to a neurosurgical centre).

Currently there is not enough evidence to given this as routine, so have this discussion with the accepting neurosurgical team and follow local practice.

Raised ICP may occur in patients with SAH and is associated with adverse outcome in small studies

What is raised ICP?

- ICP is commonly considered raised if > 22 mmhg

Surgical management options for raised ICP

- Drainage of large blood clots

- Insertion of an EVD

- Decompressive craniectomy

Medical management options for raised ICP

- Head positioning, as previously discussed, may have some role.

- Avoiding jugular compression by maintaining inline head position, avoiding restricting neck ties etc

- Sedation and paralysis

- Osmotherapy (mannitol, hypertonic saline)

- Barbituate coma

The specifics of each of these are beyond the scope of this module, though are covered in depth in the Elevated Intracranial Pressure Module.

5 days after being admitted and having her aneurysm coiled, Katherine’s level of conscious changes. Her GCS changes from 14, where she was mildly disorientated but had her eyes open spontaneously and was obeying commands to now being much less conscious. She will open here eyes to a loud voice and localise to a painful stimulus and is now just saying “no” to all questions: GCS 11, (see GCS module). She has had a low grade fever periodically since admission and is currently afebrile.

List potential causes of her decreased level of consciousness, starting with the most likely…

Treating complications

A radiological diagnosis showing dynamic narrowing of intracerebral vessels

Common: occurs in about 70% of patients admitted to hospital with aSAH (Reference)

Peak timing days 3-14 post ictus (days 6-8 highest incidence)

Gold standard for diagnosis is by digital subtraction angiogram (DSA)

Can also be seen on CT and MR angiography and suspected with transcranial doppler measurement

Risk factors include radiological grade of SAH, location and extent of blood, younger age and smoking.

May be treated to prevent ischaemia, see DCI below

> Management very different in different centres.

Treatment examples:

- Hypertensive therapy, usually with noradrenaline (e.g. Target NISBP 140-160 mmHg); if DCI present, BP target may be guided by symptoms resolution.

- Intra-arterial vasodilators e.g. verapamil, milrinone. Allows dynamic assessment of spasm reversibility

- Less commonly

- Balloon angioplasty for large vessel spasm refractory to treatment, performed with DSA

- Intra-arterial papaverine, targeted injection at time of DSA

Definiton:

> Neurological deterioration and a reduction in the Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score by ≥2 points, sustained for longer than 1 h (within a 4-h window)

Or

> A new focal neurological deficit which lasted longer than 1 h,

Or

> A new ischemic episode on neuroimaging data that was not related to the primary aSAH or neurosurgery

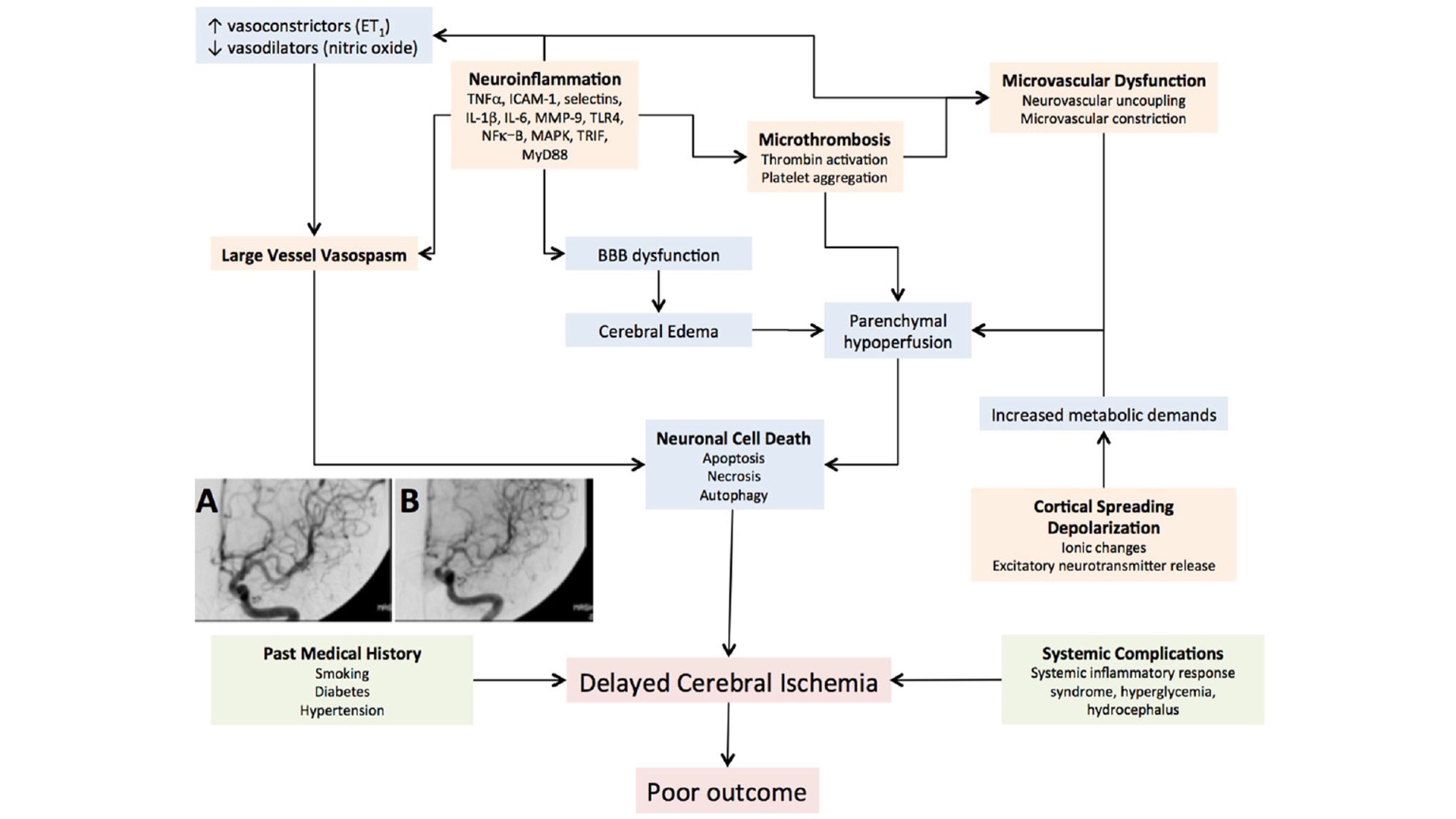

Aetiology

Interesting Facts:

> Angiographic Vasospasm (aVS) occurs in c. 70% of aSAH patients

> DCI only occurs in c.30% of patients

> Not all patients who get aVS get DCI and not all patients who get DCI have aVS

> DCI does not always fall in the same territories of aVS

> DCI predicts outcome from aSAH much more than aVS

> No evidence that angiographic or pharmacological treatments that improve aVS improve neurological outcomes from aSAH

A more in depth overview of delayed cerebral ischaemia is covered elsewhere.

Hydrocephalus is a common complication (approximately 20%) and may be present at admission or occur later on.

Acutely it may present with decreased level of conciousness, though many show no signs of this.

Factors associated with acute hydrocephalus include:

- Increasing age

- Intraventricular blood, thick focal accumulations of subarachnoid blood

- Posterior circulation aneurysm

- Hyponatraemia, hypertension

Management of acute hydrocephalus is usually with EVD insertion and CSF diversion, with an ICP aim of 15-25 mmHg.

Chronic hydrocephalus secondary to aSAH is beyond the scope of this module

What is it?

- Inflammation of the ventricular drainage systems, usually secondary to bacterial infection of the CSF

- Patients with an EVD post aSAH, who undergo intracranial surgery, or who have an intraventricular haemorrhage are at increased risk of ventriculitis

EVD ventriculitis

- Increased risk with increased length of insertion

- usually due to s. aureus and other coagula negative staph.

Symptoms/Signs?

- headache

- Fever

- Nausea/vomting

- Raised ICP / focal neurological signs

Investigations

- Bloods including cultures, CRP, WCC

- CSF culture and analysis

- Brain imaging (CT/MRI)

Management

- Removal +/- replacement of EVD if present

- Intravenous antibiotics according to sensitivies, local antibiotics resistence, micro/ID input

Prevention

- Remove EVDs ASAP

- Only access the EVD when absolutely necesary with meticulous sterility

- Antibiotics impregnated EVD catheters may reduce risk.

Treat all acute seizures, as previously covered in this module.

If seizures occur, consider future prophylaxis as previously discussed.

If it occurs is devastating, with high morbidity and mortality

For untreated ruptured aneurysms, the maximal frequency of rebleeding is in the 1st day (between 4% and 13.6%)

More than 1/3 of rebleeds occurring within 3 hours and 1/2 within 6 hours of symptoms onset.

After the first day, the subsequent risk is 1.5% daily for 13 days

Untreated, 15–20% rebleed within 14 days, 50% will rebleed within 6 months, thereafter the risk is ≈ 3%/yr

There is a risk of rebleeding during any period that the aneurysm is untreated.

Preoperative ventriculostomy, e.g. for acute post-SAH hydrocephalus increase the risk of rebleeding.

The risk of rebleeding in SAH of unknown etiology and with AVMs, as well as the risk of bleeding with incidental multiple unruptured aneurysms, are all similar at ≈ 1%/yr; may actually be less in SAH of unknown aetiology.

CHANGE OF FOCUS: PALLIATIVE CARE

In some instances, particularly after high grade aSAH in patients with existing comorbidities, aggressive medical and surgical management may not be in the best interest for the patient.

Accordingly, being able to provide high quality end-of-life care for these patients and their loves ones is paramount.

To learn more about this, please see topic End of Life in Neurocritical Care.