The beginning is not the end

> Many people live with SCI for several decades.

> Due to the nature of their injury, they have typical changes to their physiology, and are susceptible to specific conditions that may bring them back to critical care services.

> These patients are commonly managed by Spinal Rehabilitation Specialists, but occasionally come to ED’s and ICU’s.

A basic understanding of their physiology and common presentations is therefore important.

A 27 year old gentleman who had a C5 ASIA A SCI 4 years ago presents to your rural emergency department with headache, facial flushing and a facial sweating.

His blood pressure is 155/80 mmHg, HR 60, Sats 98%, RR 18.

What’s the most likely diagnosis?

What’s the initial management?

What’s the most common cause?

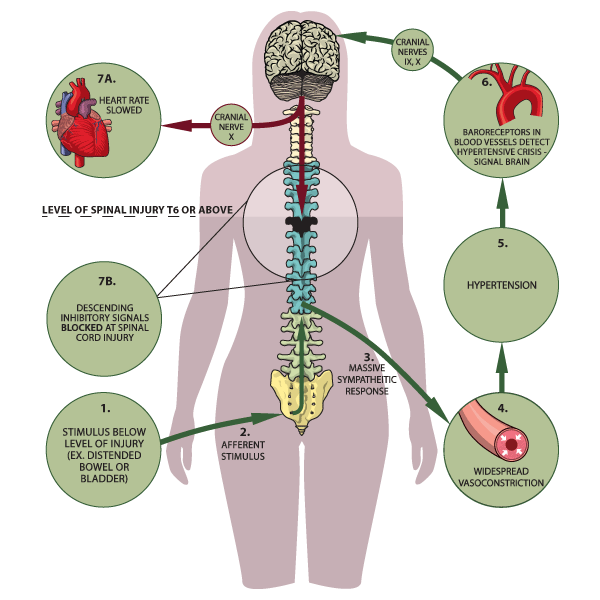

Autonomic dysreflexia results from widespread reflex activity of the sympathetic nervous system below the level of injury, triggered by an ascending sensory (usually noxious) stimulus.

Following stimulation, overactivity of sympathetic ganglia remains uncontrolled due to isolation of the spinal cord below the injury from normal regulation by vasomotor centres in the brainstem.

So below the NLOI, release of substances, such as noradrenaline, cause severe vasoconstriction with skin pallor, piloerection and vasoconstriction of the splanchnic bed causing a sudden rise in BP.

When the rise in BP is sensed by baroreceptors in the aortic arch and carotid bodies, parasympathetic activity above the level of SCI occurs:

> Compensatory bradycardia (via the vagus nerve).

> Dilatation of blood vessels above the NLOI causing flushing and headache

> Profuse sweating above the NLOI via sympathetic inhibitory outflow from vasomotor centres

These mechanisms aren’t enough to control the paroxysmal hypertension due to massive sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction of the splanchnic bed.

This can cause a hypertensive crisis, with the most life-threatening complication being intracerebral haemorrhage.

It is worth noting that as patients with chronic SCI usually have a low BP, when they have a SBP of 150 mmHg, this is a dramatic increase with a higher risk of complications.

Clinical Features

> Hypertension: Greater than 20 mmHg above baseline for both systolic and diastolic (Typical BP in tetraplegia patient is 90-110/60-70 mmHg supine)

> BP is commonly lower when patient is sitting (due to orthostatic hypotension)

> Severe bilateral pounding headache

> Diaphoresis or flushing above the level of the spinal cord lesion (Diaphoresis can be profuse)

> Nasal congestion

> Visual changes or disturbances

> Bradycardia or tachycardia (Bradycardia at onset, tachycardia may follow)

> Pallor or gooseflesh below the level of the spinal cord lesion

> Respiratory distress or bronchospasms

> Anxiety (Apprehension over impending physical problem to fear of death is common)

> Metallic taste in mouth

> Significantly elevated BP with minimal or no symptoms (Silent Autonomic Dysreflexia)

Causes

The most common cause is over-distension of the bladder, accounting for 75%-85% of episodes REF

Think of the 7B’s:

Bladder (urinary tract infection or retention, stones, distension caused by catheter blockage, urological procedure)

Bowel (constipation, impaction, rectosigmoid gaseous distension)

Boils (and any skin damage: ingrown toenail, burns, pressure area, tight clothing, sunburn, frostbite)

Bones (fractures, heterotopic ossification, dislocation)

Baby related (pregnancy, sexual intercourse, breastfeeding, severe menstrual cramping)

Back passage (haemorrhoid or fissure, rectal irritation e.g. enema or manual evacuation)

Balls (epididymoorchitis, scrotal compression, testicular torsion)

Also think of:

Syringomyelia (do MRI, especially if worsened neurology)

Medications: Nasal decongestants, Misoprostol, Sympathomimetics, Stimulants

Management

Initial steps:

Ask patient and carer if they suspect a cause.

Elevate the patient’s head and lower the legs (this will help lower BP while cause is identified).

Loosen any constrictive clothing, such as an abdominal binder or compressive stockings.

Check bladder drainage equipment for kinks or other causes of obstruction to flow, such as clogging of inlet to leg bag or overfull leg bag.

Monitor BP every 2 to 5 minutes.

Avoid pressing over the bladder

Treat any potential bladder or bowel precipitant MORE HERE

If SBP still > 150 mmHg:

GTN sublingual spray 400 mcg

or GTN patch 5mg / 24h

or sublingual Captopril 25 mg

If AD persists will need critical care, art line, parenteral antihypertensive e.g. GTN infusion

More than 85% of people with SCI will develop a pressure injury in their lifetime.

At any one time, more than 30% of people with SCI in Australia have a pressure injury.

These may be difficult to heal and require multiple operations for debridement and skin grafting.

Patients often have to stay in hospital for prolonged periods around these procedures.

They may lead to deep wound infections and osteomyelitis.

Responsible organisms may be highly resistant and difficult to treat.

Patients with SCI are at high risk for both community-acquired and healthcare-associated infections.

Risk factors include frequent contact with the healthcare system and frequent and chronic use of invasive medical devices such as urinary and intravascular catheters

Common infections:

> Pneumonia

> Bloodstream infection

> Urinary tract infection

> Skin and soft tissue infections

Infections may be missed in patients SCI due to autonomic abnormalities resulting in atypical vital sign responses, altered sensory input, history of microbial colonization of chronic wounds, and chronic urinary tract infections.

The SCI population is also particularly vulnerable to misdiagnosis and inadequate empiric therapy.

A thorough understanding of the underlying pathophysiology and chronic complications of SCI, a complete physical exam, and focused review of historical data are all crucial components in the identification and treatment of infection in patients with chronic SCI.

For more on the emergency investigations and management of infections in chronic SCI, see here

Syringomyelia is the development of a longitudinal fluid-filled cyst, also referred to as a syrinx, within the grey matter of the spinal cord.

The syrinx can expand rostrally or caudally and cause neurological injury with progressive weakness (an ascending NLOI), new sensory alterations, pain, bladder & bowel dysfunction or even autonomic dysreflexia.

Worsening neurological function can be a disaster in those with already significant compromise from their initial injury.

Syringomyelia occurs as a delayed complication after traumatic SCI in 22-30% REF

Mean time to diagnosis post SCI is 9-15 years.

What causes it?

The most widely accepted theory is the spinal trauma causes subarachnoid scarring, leading to obstruction of CSF flow.

Reactive ependymal proliferation may cause segmental closures within the central canal, local distension, and passage of CSF into the grey matter of the spinal cord via enlarged perivascular spaces

The formation of arachnoid adhesions may further alter CSF flow dynamics such that CSF enters the spinal cord causing progressive syringomyelia

Alternatively, ischemia within watershed regions of the spinal cord promotes release of destructive enzymes, free radical products and other toxic agents causing cell apoptosis and extracellular fluid to coalesce into a syrinx

More commonly the syrinx extends superiorly from the level of SCI

> It is diagnosed with MRI (see below)

Management

> If syringomyelia causes worsening weakness, surgical decompression is recommended

> The preferred surgical technique for treatment of PTS is spinal cord untethering with expansile duraplasty REF

Patients with chronic SCI most commonly present peri-operatively for:

Pressure area plastic surgery

Urological surgery for renal calculi, insertion of SPC, cystoscopies

Orthopaedic surgery (osteopenia, risk of falls)

Defunctioning colostomy for neurogenic bowel

Revision of spinal surgery

Insertion of intrathecal baclofen pumps for muscle spasticity

Specific factors to consider:

> May have difficult airway after cervical spine fixation; may have scarring / stenosis from previous trache.

> OSA and recurrent LRTI’s common; higher risk of perioperative respiratory issues

> Chronic hypotension so less room for GA hypotension

> Risk of AD – see above. Don’t kink the IDC! Continue bowel care periop

> At risk of, and may have, pressure areas – more periop vigilance required

> Often have multi-resistant organisms